THE FOREST GROUSE

The spruce grouse, dusky grouse, sooty grouse, and ruffed grouse are found in mountains and forests throughout much of North America. Although these species have been less affected by the range-wide concerns of the prairie-dwelling grouse, there are many localized concerns associated with management activities including forestry practices, livestock grazing, harvest, habitat fragmentation, and global warming.

Ruffed Grouse by Robin Tomasi.

Range: Ruffed Grouse are widely distributed across North America. Ruffed Grouse occur in 38 of the 50 states and in all Canadian Provinces. They range throughout the Appalachian Mountains from Alabama to Labrador. They used to occur widely throughout the Midwest as far south as the Ozark Mountains but the now only occur in isolated patches through the Midwest until you reach more north states such as Wisconsin and Minnesota. Ruffed Grouse also occur throughout the Rocky Mountains going as far south as central Utah and the Mountains of the Pacific Northwest going as far north as Alaska and as far south as the Klamath region in California.

General Description: Ruffed Grouse are one of the smaller grouse in North America with birds weighing from 450 to 800 grams. In general, they are brownish birds but can also be grayish or reddish. Grayish birds are typically found in colder climates while reddish birds are typically found in warmer climates such as the Southern Appalachians. Males are often larger than females. Ruffed grouse have shiny black or dark brown neck feathers that are especially large in males. Both sexes have crests but the males typically have a higher crest. Plumage of both sexes is similar but males typically have dark unbroken subterminal bands near the end of their tails whereas females typically have broken subterminal bands. Ruffed grouse tails are relatively long and rounded. Males typically have longer tail feathers than females (males: Over 14.5 cm; females: Under 14 cm).

Ruffed Grouse Range.

Diet: Diet consists of Buds, twigs, catkins, leaves, ferns, soft fruits, acorns, and some insects. Juveniles feed primarily on insects.

Primary Predators: A wide range of predators prey on Ruffed Grouse adults, chicks, and eggs. One of the primary groups of predators of adults is the raptors but many mammalian and reptilian carnivores are also predators of all life stages.

Breeding and Nesting Characteristics: Males are territorial throughout their lives and engage in a behavior called “drumming” to show their control over a territory. They typically drum from an elevated spot such as a log or a rock that is in somewhat dense brush. The drumming noise is made as they beat their wings against the air. Ruffed Grouse drum all year but it becomes much more frequent during the spring breeding season when males are advertising their territory to sexually receptive females. Females select males based on their territories and breeding is very brief. The females then leave the male to find a nesting location. Nest sites are depressions in the leaves that are often found around cover where the female can see approaching danger such as in dense shrubs or at the base of a tree or stump. Females lay a total of 8 to 14 buff colored eggs and typically lay one or two per day. The incubation period lasts 24-26 days after the last egg is hatched. The chicks are fully feathered and capable of foraging on their own at hatching. They are capable of flying after just 5 days and can cover long distances (e.g., ¼ mile) per day on the ground.

Habitat: Ruffed Grouse live in forested habitat in regions that have a pronounced winter often including deep snow. The forest types that Ruffed Grouse inhabit can vary significantly across the range by typically they are found in mixed deciduous early successional habitats. Through much of their range these early successional habitats often include aspens.

Current Problems and Threats: Ruffed Grouse populations have declined significantly throughout their range. Population declines since 1700s have resulted from the loss of natural disturbance regimes and early successional forest habitat and by increases in non-native and subsidized predators such as the eastern coyotes.

Male Spruce Grouse by Mike Schroeder.

General Description of Species, Subspecies and Related species: The spruce grouse is relatively small compared to other North American grouse, most adults weighing 450-650 grams with males averaging ~50g larger than females. Both sexes are heaviest in autumn-winter and lighter in early summer. Sexes are color dimorphic, readily distinguishable in the field. Males are heavily black and dark gray with enlarged scarlet eyebrows (superciliary combs) in spring, and females being various shades of brown and white. Taxonomy has changed frequently; Spruce Grouse presently are recognized with two subspecies, the Franklin’s Spruce Grouse of the northern Rocky Mountains in Alberta-British Columbia and the Canada Spruce Grouse everywhere else. Subtle color and size differences occur across the continental range. A possible third, intermediate, subspecies occurs in the Alexander Archipelago, southeast Alaska. The two recognized subspecies show two principal differences. First, male Franklin’s give two sharp, loud wing-claps at the end of their short territory advertisement flights down from trees, whereas, male Canada Spruce Grouse produce only a soft, short fast whirring of wings before they land. Second, both sexes of Franklin’s Spruce Grouse show white-tipped upper tail coverts, especially males, lying on top of tail feathers lacking a clear terminal band, whereas, the Canada subspecies elsewhere in the Spruce Grouse range, does not show such strong tipping of upper tail coverts and has a stronger rufous-colored terminal tail band. Genetic relationships are uncertain, but among North American species, Spruce Grouse pair closest with Ruffed Grouse; occasional hybrids occur between Spruce Grouse and Ruffed Grouse, Dusky (Blue) Grouse, and Willow Ptarmigan. Continental distribution of Spruce Grouse overlaps that of several other grouse species; most probably involves parapatry. Sympatry may be greatest with Ruffed Grouse; the two species often share the same conifer stands in Maritime Canada. Female Spruce Grouse can be confused at a distance with Ruffed Grouse, but Spruce Grouse lack the erectile crown feathers of Ruffed Grouse.

Diet: Spruce Grouse feed on conifers throughout the year but almost exclusively on needles from late autumn to early spring, principally on short-needled pines and spruces, occasionally on long-needled pines. Birds increasingly roost in trees before first winter-snows. Insects, arachnids, leaves and fruits of ground plants are important in summer. Individuals may be highly selective, for example, pre-laying females on flowers of Epigaea repens, and all individuals on flowers and fruit of Vaccinium spp. and on needles of yellowing larch in autumn.

Breeding Characteristics: The Spruce Grouse is a rather quiet species, and both sexes are territorial. Females advertise territory by giving the loudest sound, a cantus, a long, complex song, most often near dawn and dusk during the pre-laying and laying stages of nesting. Males advertise territories with their wing-clap/flutter flight. Males may advertise in autumn, but this is rare. Spruce Grouse do not form pair bonds; breeding is brief; females find their own nest site, often distant from the male.

Female Spruce Grouse on nest, Mike Schroeder.

Nesting Characteristics: Nests are depressions in ground vegetation, often at the base of a tree or stump. Nests usually have protective cover overhead and surrounding the nest but are open enough for the female to detect predators. Such concealment, however, does not guarantee nest success. Egg laying begins about 2-½ weeks after ground cover becomes 50% snow-free. Females lay 4-8 eggs, typically one every 1-½ days and usually in the afternoon. Eggs have irregular dark-brown blotches on a light tawny background, noticeably different than for sympatric Ruffed Grouse. Some females may re-nest if the first is unsuccessful; clutch size is smaller for re-nests. Incubation lasts 21-23 days, beginning after the last egg is laid; females leave nests for short periods during incubation to forage, averaging 25 minutes each, three times daily. All eggs that hatch do so within about 24-hours of each other. Two-thirds of all females hatch clutches within a 7-day period. Clutch-size and net production at end of summer generally is lower for Franklin’s than for Canada birds.

Brood-Rearing Characteristics: Newly hatched chicks have eyes open, are covered with down, show 7 juvenal primaries and weigh an average of 15-grams at hatch. Chicks and hen leave the nest together within 24-hours following hatch; chicks feed themselves. They are capable of flying short distances at 6-8 days post-hatch. Brood stays together for 70-100 days. Juveniles begin to disperse without aggression, often departing separately when brood cohesiveness wanes and communication between juveniles and parent do not elicit usual responses. Dispersal is complete in November before permanent snow cover. Some juveniles do not disperse far and may re-occur with their parent in winter.

Range: Spruce Grouse are distributed widely across the northern short-needled conifer forests of North America, in taiga, boreal, and montane communities, progressing northward to tree line. Southward distribution in the east and in the western cordilleras terminates where expansive northern short-needled pines and spruces give way to other plant communities. Spruce Grouse overlap the northern range of Ruffed Grouse. Spruce Grouse occupy 12 northern states but are sparse in several; they occur in all Canadian provinces and territories except Prince Edward Island, and are sparsest in Nova Scotia.

Spruce Grouse Range.

Habitat Characteristics: Spruce Grouse are found in conifer forest, young and old, from near tree -line to wet lowlands. Generally, they use short-needled conifer communities such as jack and lodgepole pine and spruce-balsam fir-tamarack, and may occupy conifer-deciduous mixed forest. Unique forest communities to note are their affinity for low-lying black spruce-fir-tamarack in southern areas (northeastern states and the Lake States) where populations are sparse; the mature hemlock-cedar-Sitka spruce in temperate rainforest, southeast Alaska; and the Engelmann spruce-subalpine fir at high elevations in the western cordilleras. With some exceptions, such as southeast Alaska, presence and perhaps density of Spruce Grouse are associated best with moderately-low tree height [<14m], live canopy ≥50% of tree height, and/or tree branches ≤4m above ground. Occupied forest, whether immature pine or old spruce, is similar in having moderately-high tree and/or shrub density with branching that provides horizontal cover in the understory a short distance above ground. Birds may select different forest structure in different seasons, most divergent being open display centers for males in spring and some open brood coverts in summer. Ground layers of occupied forest range from reasonably-simple ericaceous-lichen mixtures on very well drained sandy soils or predominantly grass-sedge layers in pine forest, to more complex layers in old, wet spruce-fir-tamarack lowlands. Shrub layer appears especially critical to site occupancy.

Predation: A wide range of predators including mammalian, avian and reptilian species, prey on Spruce Grouse adults, chicks, and eggs. Raptors are important predators on adults and juveniles, mammalian predators primarily on juveniles and eggs. Red squirrels are an important egg predator in certain populations and most often destroy or remove only partial clutches. Predation is considered to be the major cause of mortality, but evidence is not strong that it alone drives Spruce Grouse density. One indirect effect is predation on nests, as high as 70% in one Franklin’s population, with its carryover effect on end-of-summer net production and, carrying on, the subsequent recruitment rate of first-time breeders into the adult cohort the following spring.

Population Status: Spruce Grouse were studied little until the latter half of the 1900s, hence, it is difficult to compare contemporary populations with earlier history. In addition, Spruce Grouse are not observed readily by most people, and they are hunted little except in some very local situations. Nevertheless, abundance likely has decreased where towns and human land-use have spread. Of 12 northern states with Spruce Grouse, special protected status occurs in 7; in 6 of these states, including Wisconsin and all occupied states eastward, populations are low and sport hunting is not permitted. It is unlikely, however, that hunting has been a dominant cause to low abundance in these states. Densities of total adult Spruce Grouse reported in the last 50 years vary considerably across their continental range, from 0 to over 80/100 ha. Densities may change among years or differ between nearby study sites by as much as 2- to 10-fold. Highest recorded densities (80/100 ha) are in aerially-seeded jack pine stands, overlying almost pure sand, as young as 10 years and 4-8m tall in central Ontario. The most apparent patterns in continental densities are: generally, they are low in spruce-fir-tamarack forests, higher in pine forests; are higher in young than in old forests of the same tree species composition; and occupied patches in the south where the species is threatened often show densities no lower than those in extensively occupied spruce-fir forest further north.

Current Problems and Threats: Across the northern half of continental range there is little knowledge about the status of Spruce Grouse populations, largely because birds inhabit a vast area with few people and little hunting, and the species is not counted. But Spruce Grouse indeed are responsive to natural forest dynamics and anthropogenic effects. One emerging large-scale scenario to watch is the death of lodgepole pine trees across large areas of British Columbia and Washington from extensive fires and from mountain pine beetle and subsequent salvage harvests. At a reduced scale, clear-cut forest harvesting is known to reduce local density of territorial adults. But productive research in Quebec shows that well-designed forest interventions can be beneficial: birds remain in many residual buffer strips as small as 50m wide. Spruce Grouse also colonize certain young pine and spruce plantations. The gravest problems to Spruce Grouse are brought on by the absence of progressive forest management and/or by restricting natural processes. Public policy that curtails wood harvest, promotes tight fire control, or only promotes old age forest, clearly limits the ability of Spruce Grouse to persist. This appears partly the case at least in New York. Most eastern states with Spruce Grouse have developed management plans to retain Spruce Grouse; Vermont has established an on-the-ground management protocol for their small, occupied spruce-fir forest. Quebec research is appropriate for guidance in the states with sparse populations. There comes a point at which the importance of tree species composition itself becomes overtaken by the magnitude of increasing fragmentation, the distances between remaining occupied patches. Spruce Grouse are a short distance disperser. Hence, a first step may be to modify unoccupied patches immediately adjoining the remaining occupied patches to enhance the ability to disperse successfully, as stepping-stones outward to other remaining occupied patches. Regardless, without any on-the-ground management trials based on knowledge already available, Spruce Grouse will be lost in its southern range.

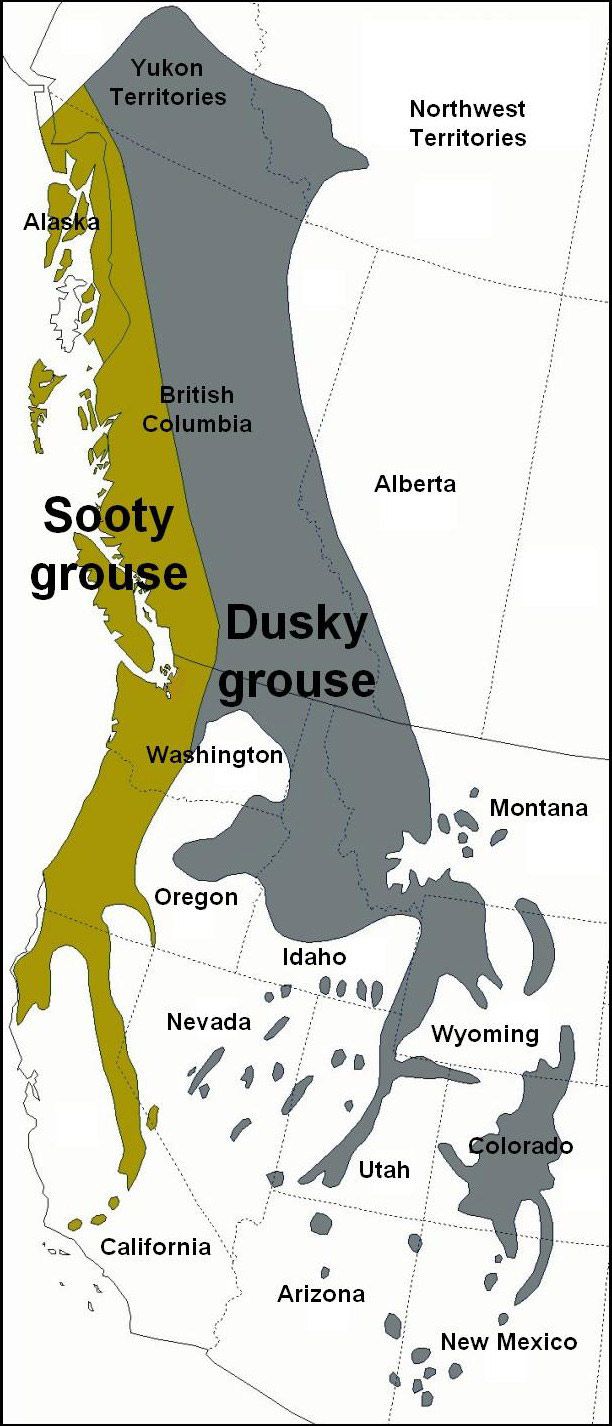

Ranges of the Sooty and Dusky Grouse.

Life History Coming Soon!

Life History Coming Soon!